Tech To Table: Global Trade and Your Smart Kitchen

A Grape’s Journey

When I wake up each morning, I like to make myself a cup of coffee and a bite to eat. I normally do not think twice about where I start my day. My handy and cozy kitchen. Now I have to admit I am not much of a cook. I have been known to fix up an omelet or some French Toast or perhaps fry a salmon steak in a pinch. But normally I am treated to all kinds of home cooked meals by my wife who enjoys putting the kitchen through its paces on most nights.

I started to think, what does this kitchen represent from the point of view of Tech & Society. That is, where do all these common technologies (and food products) we surround ourselves with every day to sustain one of our most fundamental human needs – nourishment – actually come from and what are their impacts on our society? Moreover, I began thinking how these various technologies and the web they weave across the globe would be viewed by Henry George the 19th century Economist.

As an example, on a recent morning I enjoyed some fresh grapes as part of my breakfast. Looking at these little shiny globules of sweetness I contemplated – where did this little grape really come from? Well, for me, grapes (Vitis Vinifera) known since pre-history in Asia and harvested from at least the Paleolithic period, come from California. They may be picked by migrant workers from Central America, trucked to the East Coast on vehicles burning diesel fuel originally pumped from wells in the Middle East. Fuel shipped around the world by super tankers built in South Korea. Furthermore, I had served this little grape to myself in a small decorative porcelain dish (a Chinese invention) made in England which we bought recently in a flea market in Paris that we had reached on an American built jetliner assembled from 3 million parts from 58 countries.

So, putting all that into perspective I became somewhat gobsmacked that a little grape could require such a massive Global technical and economic infrastructure just to find its way to my stomach.

Kitchen Tech

Most technologies have a similar diverse geographic heritage. In fact, the earliest kitchens are known to have existed from archeological finds dating back a half a million years in China. Of course, prior to this we simply cooked around a fire pit. Eventually the Romans established their country estates to grow grapes and brought the resultant wine to their city villas with dedicated kitchens. Skipping ahead, Benjamin Franklin invented the Franklin Stove which for the first time provided efficient concentrated heating with external venting. Soon after this the Swedish cast-iron stove would be recognized by all of us today. With the invention of the refrigerator in 1911 by GE, the kitchen we know today was on the horizon. However, for Americans it was not until the 1940s that refrigerators were commonplace due to affordability. In fact, my father referred to his refrigerator as an “ice box” throughout his life – meaning an insulated box with a block of ice periodically delivered by the ice man.

Fast forward to today and our kitchens are chock-a-block with technical gizmos sourced from around the world. Some of these items people buy and then eventually banish to a back shelf after tiring of their use. However, the global nature of this kitchen technology has not changed. Just like Ben Franklin and the Swedes revolutionized the stove in centuries past today innovation comes from all quarters.

With our “smart” kitchens today, for example, an AI (Artificial Intelligence) enabled smart refrigerator from a major South Korean manufacturer (Figure 2) can do more than any icebox might dream of. The concept behind this device suggests that it can be integrated through the Internet of Things (IoT) to communicate with other devices in the kitchen and also to sense when you might be low on milk and potentially reorder for you. Personally, I am not sure what my refrigerator really has to say to my toaster, but I will leave that for the reader to consider. I do question the necessity for my refrigerator to take over my grocery ordering. Does that mean I always have to eat what it selects? And does this mean I need a similar “smart” device in my cupboard to reorder my cans of soup? How far does this go?

There is an interlocking lattice of invention, development, and supply which is of course only one aspect of how our kitchens come together. Our Global Free Trade environment of the Post War era has accelerated this model and lifted millions out of hardship and drudgery if not always uniformly. At the same time, we have seen a parallel and related impact on ecological conditions. By sourcing our kitchen knives from metal ore in Africa then shipping this to Asia for productizing and finally delivering it to your strip mall, a tremendous amount of energy is consumed. Henry George actually touched on each of these areas – trade, inequality, and the environment as we will discuss.

Our Global Food Supply

“Them belly full, but we hungry”

Bob Marley, 1974

Now that we have explored this dazzling array of technology in our commonplace kitchens, let us think about the food products and produce that we routinely procure for our cupboards and fridges to create our daily meals. Just like our savory little grape who got this story rolling, so too most other foodstuffs we consume travel far to find us despite recent interest in local sourcing.

Think of Christmas time. Ah, the Yule log and trimming the tree by the fire. Of course, this scene would not be complete without a glass of eggnog with a pinch of nutmeg and cinnamon, right? And where does nutmeg come from? Indonesia, India, and Guatemala each produce about 1/3 of the World’s supply. However, the history here sheds light on our current Global food supply system as well as aspects of Free Trade and Economic inequities written about extensively by Henry George.

Think of Christmas time. Ah, the Yule log and trimming the tree by the fire. Of course, this scene would not be complete without a glass of eggnog with a pinch of nutmeg and cinnamon, right? And where does nutmeg come from? Indonesia, India, and Guatemala each produce about 1/3 of the World’s supply. However, the history here sheds light on our current Global food supply system as well as aspects of Free Trade and Economic inequities written about extensively by Henry George.

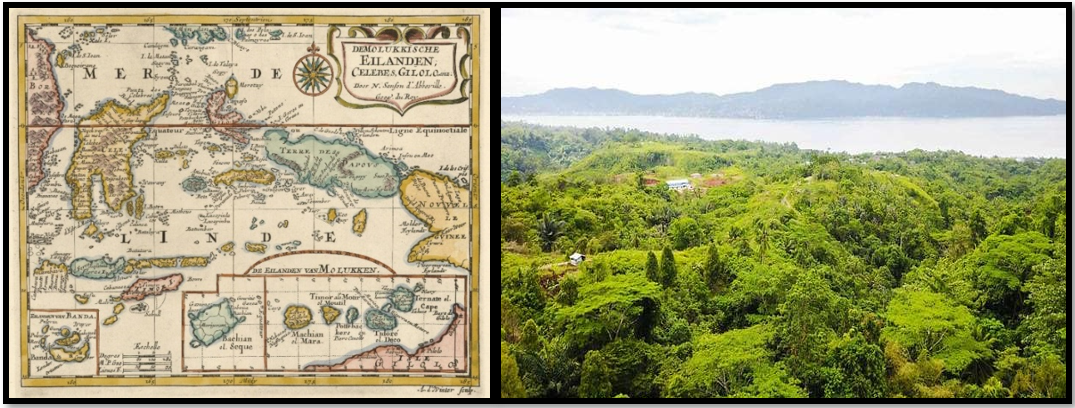

For millenia, an archipelago known as the Moluccas to the East of Sulawesi and now part of Indonesia traded with other parts of Asia including China. Their main crops were spices including nutmeg and cloves. Hence their eventual name the Spice Islands. In the Middle Ages the Arabs controlled this Spice Trade depositing the produce in Venice making that city a hub of wealth in Europe while the Arabs kept the location of the islands a strategic secret. After numerous explorations and arm-wrestling wars over the islands involving the sacking of at least one island capital and innumerable lost lives the Dutch eventually won control of the islands in the 16th century and administered them through the Dutch East India Company.

Figure 3 – An early historic map of the Spice Islands (Left). Ambon, Indonesia, the original Spice Island today, once more valuable than Manhattan (Right).

Today the native species of spices which originated in the Moluccas are cultivated in other temperate regions. However, 99% of the world total of cinnamon, for example, is still produced in Indonesia, China, Vietnam, and Sri Lanka. So, if you like that cinnamon pop-tart in the morning, thank somebody in Sri Lanka or on Ambon Island in Indonesia.

Bringing this full circle, the state of spice farming in the original home of these plants – islands like Ambon in Indonesia – have fallen on hard times. Several countries produce cloves today and Indonesia remains the largest among them. But on Ambon, the originator of clove agriculture, only small-scale farms remain with many farmers “living in poverty” according to the local governor. Instead, the youth must follow other pursuits and leave cloves and nutmeg behind to secure their livelihoods joining into new modes of economic interaction propelling the continued global trade which the original Spice Islands have seen since before the rise of the Roman Empire.

Free Trade, Environment, and Keeping You Fed

Turning the discussion from kitchen technology, logistics, and food production to the economic principles supporting these human products and endeavors, a reasonable place to start is with Adam Smith. As with most Economists we can find messages from Smith supporting many positions, yet one thing is clear. He believed that people wanted to and should be allowed to buy goods from sources at the lowest prices. This translated into his support for Free Trade. A century later Henry George, the American Economist and Political Philosopher, best known for his work “Progress and Poverty”, also wrote extensively about Free Trade. Here in the introduction to his master work he “sets the table” so to speak:

“…there is distress where protective tariffs stupidly and wastefully hamper trade, but there is also distress where trade is nearly free…” – Henry George, 1879.

“…there is distress where protective tariffs stupidly and wastefully hamper trade, but there is also distress where trade is nearly free…” – Henry George, 1879.

In his full-length treatment of the subject, “Protection or Free Trade” in 1886, Henry George took on the subject of tariffs and how they related to wages, prosperity, and inequality. George wrote that “Protection … means the levying of duties upon imported commodities for the purpose of protecting from competition the home producers of such commodities.” Proponents of such a strategy contend that nations should procure essentially everything for themselves to promote their prosperity. In George’s time they also argued that high wages would also be delivered. However, George was not supportive of this method and in fact linked such policies to numerous social ills:

“Protection, moreover, has always found an effective ally in those national prejudices and hatreds which are in part the cause and in part the result of the wars that have made the annals of mankind a record of bloodshed and devastation …” – Henry George, 1886.

Personally, I find this perspective uniquely uniting of the sinews of history from the Spice Islands all the way to today’s conscious choice of American Multinational Corporations to source production and supply globally. In fact, George observed that from a tax angle, “it costs more to get goods through a custom house than it does to carry them around the world”. Essentially, George was more “anti-protectionist” than a free-trader who agreed to free trade when certain conditions are met. Importantly, he strongly believed that free trade would not benefit workers unless we have a land tax.

True to form, Henry George also found the relationship between protectionism and inequality. In today’s public debate on the subject this is one aspect that is often downplayed. That is, if the US protects its businesses through tariffs this somehow must translate into economic goodness for the average citizen and worker. However, even in George’s time the baselessness of this calculus was well understood:

“[this] cuts the last inch of ground from under the fallacies of protection, while showing why free trade fails to benefit permanently the working classes. It explains why want increases with abundance, and wealth tends to greater and greater aggregations.” – Henry George, 1886.

Finally, our kitchen equipment, provisions, and the logistics that move them to us have an impact on the environment and this is also an area where George had ample thoughts. For Henry George, land, included the wealth of the earth “in all its natural forms, the air and water as well as material elements” according to Batt. In “Progress and Poverty” George himself says that “land includes all natural opportunities or forces.” And as Backhaus and Krabbe point out, these resources, when viewed from the Georgist perspective where a land tax provides economic pricing to their access, such resources can also provide negative income streams if abused as in cases where they are over utilized or polluted.

This leads us to consider the linkage between Henry George’s outlook and current day environmental economics. As described by Batt, George’s premium on the preservation of the commons, sustainable development, tempered valuation of nature’s bounty, and the delivery of social justice all align well with modern thinking in an era concerned with conservation and the looming impacts of climate change. This ties into our beckoning grape or cinnamon toast at breakfast as well. Without appropriate global trade facilities paired with respect for the environment we can end up with cross border arguments and pockets of poverty in otherwise rich farmland regions like the Spice Islands.

Conclusions

Figure 4 – Back to basics – cooking over a campfire

When all is said and done, I recall a quip I once heard to the effect that … “you only know how much free time you have when you are in a place without any time saving devices”. This makes me think back to my days of camping trips as a child, backcountry hikes in the California Sierras, or Island hopping through the Inland Sea of Japan. Far away from telephones and computers and forced to cook over an open flame there was no AI genie telling me to check on how many tomatoes were in the bin. Those were simpler moments connected to nature and void of complexity. Yet, I somehow remember I used to always pack a couple small boxes of sun-dried raisins to snack on along the trail bringing us back to our friendly little grape from the beginning of this story. So, the next time you hear someone say Globalization is bad take it with a grain of cinnamon.

References

- “Grape, Vitis Vinifera”, Fruits & Vegetables, FAO Yearbook, 2000, viewed 6/12/2021.

- “A Complete History of the Kitchen”, CopperSmith, June 5, 2020.

- “A History of the Spice Islands: Understanding Spices”, Seasoned Pioneers Blog, viewed 6/12/2021

- “Boeing, Diverse suppliers bring big value to Boeing and their communities”, Community, July 02, 2020.

- “Cinnamon”, Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, viewed 6/12/2021.

- “Progress and Poverty by Henry George 413 South”, Slide toDoc.

- Backhaus, J., & Krabbe, J. (1991). “Henry George’s Contribution to Modern Environmental Policy: Part I, Theoretical Postulates”, The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 50(4), 485-501.

- Batt, H. William, “The Compatibility of Georgist Economics and Ecological Economics”, Presentation at the United States Society for Ecological Economics, Saratoga Springs, New York, May 22-24, 2003.

- Board, Jack, “On Indonesia’s ‘Spice Islands’, farmers fight to keep legacy alive”, CNA Insider, Singapore Edition, December 29, 2020.

- Bob Marley & The Wailers, “Natty Dread, Them Belly Full (But We Hungry)”, Cayman Music, Peermusic Musikverlag G.m.b.h., Odnil Music Ltd., Fifty Six Hope Road Music Ltd., Blackwell Fuller Music Publishing Llc., October 25, 1974.

- George, Henry, Progress and Poverty: An Inquiry into the Cause of Industrial Depressions and of Increase of Want with Increase of Wealth the Remedy., D. Appleton and Company, New York, 1879.

- George, Henry, Protection or Free Trade an Examination of the Tariff Question, With Especial Regard to the Interests of Labor, (1886), Robert Schalkenbach Foundation, New York, NY, 1949.

- Johnson, Bobbie, “Why people still starve in an age of abundance”, MIT Technology Review, December 17, 2020

- Smith, A. & Cannan, E., “An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations”, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, (2021).

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!