A Real-Assets Model of Economic Crises: Will China Crash in 2015?

By MASON GAFFNEY

ABSTRACT. Loosely derived from Henry George’s theory that land speculation creates boom-bust cycles, a real-assets model of economic crises is developed. In this model, land prices play a central role, and three hypothesized mechanisms are proposed by which swings of land prices affect the entire economy: construction on marginal sites, partial displacement of circulating capital by fixed capital investment, and the over-leveraging of bank assets. The crisis of 2008 is analyzed in these terms along with other examples of sudden economic contractions in U.S. history, recent European experience, and global examples over the past 20 years. Conditions in China in 2014 are examined and shown to indicate a likely recession in that country in 2015 because its banks are over-leveraged with large-scale, under-performing real estate loans. Finally, alternative methods of preventing similar crises in the future are explored.

Introduction

Concern about economic instability is understandably limited in the minds of most people to their own country. Thus, the economic and financial contraction in the United States that began in 2008 has been the object of most interest to American economists. When they make comparisons, the experience of the United States in the 1930s tends to be the primary event that is viewed as parallel to the current crisis.

A general theory of the business cycle or economic instability should not be derived from or tested solely by two events. If a theory is valid, it should apply to numerous cases in the past and, ideally, it would serve as the basis for predicting future cycles of boom and bust, growth and decline. We cannot, like scientists in a laboratory, create the conditions we wish to study, but economists can attempt to be more scientific than we have been until now by examining as many cases as possible from many countries and time periods.

This article will begin with a conceptual model that first offers an explanation of numerous panics, crashes, or crises in the history of the United States. It will then discuss its relevance to recent expansion and contractions in several European economies. Finally, it will analyse the prospective problems facing the Chinese economy in 2015, with the hope of demonstrating the value of this model for prediction, not merely description. By applying the model to a number of different circumstances, I hope to show that it is a universal model, capable of explaining cycles of economic expansion and contraction throughout the world.

The theory presented here derives from a simple model developed by Henry George ([1879] 1979: BK V, Ch. 1). George blamed the periodic “paroxysms” in modern economies on the effects of land speculation. In his view, if enough people held land off the market in the hope of a price increase, the resulting artificial scarcity of land would raise rents and land prices, driving down wages and returns to productive investment. Eventually, this process would reach a limit, land prices would fall, workers would be laid off, and factories would close. We should give George credit for seeing the general outlines of this process, but we must elaborate on his ideas to incorporate elements other than land prices. I have elsewhere presented a thorough explanation of the model developed below (Gaffney 2009), so I shall merely summarise it here.

General Theory

To make sense of what happened to China in 2014 and the United States in 2008 and 1927, we must shift our attention away from the details of each crisis and attempt to detect, amid the noise and varying particulars, a general pattern of economic crisis. I will develop here a “real-assets” model or theory that will be useful in understanding that pattern. The hypothesis here has four elements:

1. A rise and fall of land prices, resulting mostly from autonomous real economic changes. These are less visible and less measurable than purely monetary and fiscal changes, which may reflect and even reinforce the real changes but not initiate them,

2. Investment in projects at the margins, both in terms of geographic location and value,

3. Concomitant changes in the structure of capital investment to favor structures with long payout periods, and

4. An increase in bank leverage ratios as a result of lower capital turnover, leaving many banks technically in default by the time the land price bubble bursts.

Land Price Changes

The present hypothesis begins a posteriori from observing land prices increasing over a period of five to eight years after a trough. This contrasts to common scenarios that cast the banking system as the autonomous factor initiating economic crises. Once price increments begin to seem the normal, “rational” expectation, staid banks and other financial institutions turn to lending on land collateral, and expand their balance sheets to accommodate the increased investment in real estate. But banks are responding to an external stimulus (an apparent improvement in the value of real estate) rather than creating the conditions for a boom on their own. It is only in the late stages of the land price boom that banks, when they are lending money on increasingly marginal sites, must develop creative accounting methods to circumvent the financial regulations that were put in place during a previous period of contraction to prevent reckless lending.

The first sign of a new cycle of boom and bust is a self-generated rise in land prices, which shows up in the form of higher priced houses. When we speak of an increase in housing prices, what we really mean is the change in the price of urban land on which the houses are built. Since the actual housing stock depreciates over time, it makes no sense to conflate the two. If the price of housing rises 8 percent, the price of land must have increased by, say, 15 or even 20 percent to account for the stability or decline of the portion of value invested in physical capital.

A land price occurs naturally as a result of increased economic productivity or, often enough, a period of “peace dividends” following a major war. For the first few years after a crash, the land market remains unnoticeable. Buyers are wary of investing in real estate immediately, and banks are even warier of lending for that purpose. In addition, banks are unable to lend much because they have to retrench in order to lower their leverage ratios. Nevertheless, four or five years after a crash, land prices will start creeping back upward as a result of general economic growth. Initially, that will cause an increase in the price of existing houses. (Actually, the price change will represent an increase in the value of sites, not the buildings, which are depreciating, becoming obsolescent, and often being replaced at lower cost.) Increases in real estate prices will signal to home builders and commercial real estate developers that the time has come to build new homes and offices. At that point, perhaps 10 to 12 years after the last crash, a new speculative boom begins. At this point, the rise in land prices accelerates because a rise stimulates more investment, which stimulates a faster price increase, and so on. This occurs first in residential markets, followed closely by commercial and industrial (C&I) real estate. Land price appreciation becomes noticeably higher than alternative investments, and a frenzy takes hold in which more and more people imagine they can make money without effort by investing in real estate. Many of those caught up in a frenzy fancy they are the rational ones, as revealed by the phrases they publish, like Fisher’s “permanently high plateau” of prices, and Sargent’s “rational expectations,” and Will Rogers’s “Buy land, they ain’t makin’ any more of it!”

The rise in land prices must eventually reach a limit. The ratio of loan repayments to cash flow (and service flow) eventually becomes high enough, even to the point of exceeding unity, to reverse the speculative frenzy and cause a sell-off. There is a plateau at the peak, as owners who bought for short-term gain are now reluctant to take a loss, so as the market softens, bid prices fall faster than asking prices, and sales slow down for a few years. According to the S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Index (2014), the index of home prices hovered at 206 from June to August 2006 (January 2000 5 100), before beginning a decline to 139 in April 2009. (The price of land is more volatile than home prices, since the relative price stability of the housing stock moderates the combined price of land and housing.1) Once prices start to fall, some speculators begin selling quickly, accepting declining bids in order to avoid holding property in a falling market. Others, with greater holdout power and more sanguine expectations, settle in for the long wait, hoping prices will recover. The price of land—those few parcels that do sell—then starts to fall faster than it rose. Land prices may crash in two or more waves, the housing market leading the commercial market by about two years, as happened 1927–1929 and 2006–2008.

If there were a national land price index, it would be possible to demonstrate this pattern. In the absence of such an index, we can use data on construction from the U.S. Census Bureau (2012, 2014a).2 The value of residential construction rose 95 percent from 2000 (annual average) to March 2006, then declined by 66 percent by February 2011. A similar phenomenon occurred in nonresidential construction, which includes not only commercial, industrial, and service-sector construction, but also infrastructure such as roads and sewer lines, harbors, andairports. From June 2002 to November 2008, it rose 232 percent, thenfell 29 percent by May 2011. There was a lag of 32 months between the peak of housing construction (March 2006) and the peak of nonresidential construction (November 2008).

National data on government gross investment in fixed assets (around 20 percent of private investment) shows much less volatility than private investment, which is surprising, given the importance of local infrastructure investment in fueling a boom and the immediate depreciation of abandoned public infrastructure after a crash. However, the absence of volatility in aggregate data may simply reveal the relatively small number of cities affected by “irrational exuberance” that can create a national economic crisis. National data may obscure what is going on in key local economies. There are also temporal idiosyncrasies, varying with the ideologies of politicians. Thus the canal boom of 1820–1840 was a nationwide mania in spite of President Jackson’s refusal to use federal funds directly. This is an area for future research. Note that in the case of housing, the peak of construction in 2000– 2008 occurred three to five months before the peak of the S&P house price index. This would suggest that housing starts might represent a leading indicator of an impending contraction in the economy. The same pattern of successive waves of housing and nonresidential construction cycles can be found in the 1920s, indicating that this model is useful in explaining the Great Depression as well as the most recent crisis. The value of housing construction rose 167 percent from 1921 to 1926, then declined 93 percent by 1933 (U.S. Census Bureau 1975a: Column N32). Nonresidential construction rose 93 percent from 1921 to $2.7 billion in 1929, then fell 85 percent by 1933 (U.S. Census Bureau 1975a: Column N36). The peaks of residential and nonresidential construction were thus around three years apart. Add to that, housing prices peaked in 1927, two or three years before stock prices did in late 1929.

Of course, a rise and decline in housing construction is not a perfect proxy for changes in land prices, but it is a good approximation. A large increase in housing construction occurs during the boom phase of the land price cycle because (a) building and selling houses is one way to generate immediate revenue from rising land prices, and (b) rising land prices generally encourage investment in capital with low turnover (as will be explained below). Since there are no land price indices in the United States and most other countries, construction data must serve as a proxy in following the economic events that lead up to a financial crisis.

Use of Marginal Sites During Booms

During an economic boom, as land prices are rising, an immediate effect is hoarding of good locations. If land prices are expected to rise at 20 percent per year, and other investments yield only 10 percent, owners have an incentive to hold land off the market until the growth of land prices falls below the return on alternatives. Although some properties are “flipped” multiple times during a period of rising land prices, other sites remain idle or underdeveloped while the owner waits. Since that process occurs on many of the most desirable locations, land on the margins of a city will benefit from the artificial scarcity of better locations and the rise in land prices. As a result of bottlenecks in the use of sites, boom periods lead to speculative investment in housing and office buildings in marginal areas of a city: sites on the urban periphery, sites with hazards like flood, fire, windstorms, quakes, and unstable ground subject to liquefaction. The market signals that these sites are suddenly valuable, and developers respond with new projects. There is a reason these areas are marginal.

A higher than average proportion of the households or businesses that purchase or lease the new construction lack the cash flow required to make their payments to the developers. When the land price bubble bursts, foreclosures become commonplace. Highly-leveraged builders are then also forced into foreclosure, leaving office buildings or housing tracts uncompleted or unoccupied: “Hayeks” in the 1920s; “The Empty State” building in 1930s Manhattan, and “orphan subdivisions” around Chicago and Detroit; “see-through” buildings in 1988 in Dallas and Denver. In addition, the dispersal of development when the economy is experiencing “irrational exuberance” creates a drag on the economy to the extent that economic activity becomes less geographically concentrated. Extensive development beyond the limits of ordinary (non-speculative) economic activity is inefficient and raises transportation and linkage costs of many kinds. Thus, land price rises cause geographically inefficient investment.

Changing Characteristics of Capital

Although speculative growth of land prices and investment in marginal locations are the initial factors that lead to major episodes of economic instability, a proximate cause of crisis is a shift that occurs in the nature of capital investment. The net effect is to increase the average payback period of capital investments, which creates instability in the banking system. Raising the average length of loan retirement has effects on other economic variables, such as reducing employment opportunities, a question we shall return to later.

In the following section, we will explain the effects of capital lengthening on the financial sector of the economy. In this section, we will consider only the process by which rising land prices lead to this phenomenon.

Circular (positive feedback) effect. The first relationship of land and capital is a circular process whereby the development of marginal locations lowers the rate of return on productive investments. That reinforces the advantage of further investment in land, which fuels this cycle. Potential developers buy more land than is necessary for current development plans because they are reacting defensively to the anticipation of higher prices. This biases investment still further. What looks like a virtuous cycle to the individual who invests in land looks like a vicious circle to businesses that produce things of value and that lose their financing to those caught up in a land-buying frenzy. Net effect: More investment in land, less in physical capital.

Price effect. The second consequence of rising land prices on capital investment is a price effect. As the price of land rises relative to construction materials, builders will substitute capital goods (mostly buildings and equipment) for land. (Alfred Marshall ([1890] 1920: Appendix G) foresaw this clearly.). This is a price effect that occurs whenever the relative price of inputs changes. As we have already seen from the statistics cited above, as the relative price of constructionmaterials falls compared to land prices, developerswill engage in a flurry of construction. Nothing is ever quite that simple, to be sure, since building materials like metals and lumber and cement are land-intensive in their own production, but the net effect is: Less investment in land,more in physical capital.

Wealth effect. The third effect of rising land prices is a wealth effect, according to which landowners feel richer than before and spend at least part of the rise in value of their paper assets. The wealth effect is either inflationary, if no value is produced in conjunction with higher spending, or simply destructive of capital, if consumption displaces saving. Net effect: Saving declines, as illusory income is spent on consumption goods.

Sprawl Effect. A fourth effect is the capital cost of sprawl (scattered settlement). Scattering a given population over more space calls for longer roads, pipes, wires, canals, and all kinds of connective capital, plus more vehicles, more fuels with wells and mines and refineries. It is a long list that the reader can supplement. The land idled in hollowed out cities may be replaced by suburbs and exurbs and whole counties filled with dachas and their connective infrastructure.

What is the net effect of all of these complex interactions? To find an answer, we must first distinguish between two types of capital, which are actually differences along a continuum, not distinct categories. However, for the sake of simplicity, we will refer to them as “circulating capital” and “fixed capital.” We draw the distinction sharply here to emphasize that not all capital investment is alike and that the behaviour of land markets strongly influences which kind of capital will dominate investment.

Circulating capital here stands for a one-time investment that quickly generates revenue that can be reinvested again and again. In other words, it is capital (K) with high turnover. We can think of turnover (T) as the number of times capital is recouped in a year or some other time period. It is the reciprocal of the payout period (P), or the time required to produce enough value to fully recoup the original investment.

For example, a children’s lemonade stand with a $2 investment (K) in lemons and sugar at the start of the day might yield $10 in revenue. In that case, T is 5 because the capital turns over five times in one day, and P is 1/5 of a day. In a small convenience store, if K is $100,000 ($50,000 for initial payroll and $50,000 for inventory), T might be 12, so the flow of capital (F) would be 12 3 $100,000 5 $1,200,000. We assume here that the revenue in each payout period (one month) is sufficient to pay forwages, inventory replacement, and other operating costs.

In general, capital investment (K) times turnover (T) equals the flowof capital (F) or KT 5 F. For a given level of investment, the higher the turnover and flow, the more will be available to hire labor. If the inventory in this hypothetical convenience store turned over only twice a year, the flow would be only $100,000, which is also the amount that would be available to pay wages and other costs. Thus, the ability of capital to sustain labor is as much a question of turnover as it is the size of the capital stock.

If that sounds novel to modern ears it is a sign of retrogression in economic thinking: Adam Smith, David Ricardo, Knut Wicksell, and before them, Turgot spelled it out clearly in their classic works.

Fixed capital here refers to capital that yields value slowly and thus turns over slowly. It is typified by a house, office building, or factory, where capital turns over only once every 40 years (or more). (Thus T 5 1/40 or 0.025.) Since interest is the primary cost of a long-term investment, a given level of capital yields a dramatically reduced flow, so that KT > F. For a 40-year loan at 8 percent interest, 70 percent of payments are for interest, and only 30 percent are available to yield net value of production.3 Even with an interest rate of only 4 percent or a building life of 20 years, interest would still claim 50 percent of total payments. Thus, in the case of fixed capital, interest drives a wedge between initial investment and the production of value. The lower the turnover (or, equivalently, the longer the payout period) the more capital is diverted into simply maintaining itself rather than combining with labor to add value. If fixed capital becomes too large a portion of total capital in use, this imposes a drag on the entire economy.

This brings us back to the question of land prices. When land prices start to rise during a boom, investments in circulating capital are shifted to fixed capital. The latter now suddenly seems more profitable than mundane investments in the circulating capital of productive enterprises. This illusion of highly profitable construction is created by conflating the increase in land values with returns on construction, an easy mistake to make since revenues do not announce themselves as payments for location as opposed to structures. In fact, the return on construction will be negative for many buildings produced in a boom period, since construction on marginal land is often abandoned or delayed for many years. As in a Ponzi scheme, some early construction investments may turn out to be profitable, but much of the capital invested in construction is simply wasted, gone forever.

The dissipation of private investment on fixed capital is matched by the equally foolish investment of public funds in similar projects. Even where private developers pay for infrastructure within the area of their project, local governments pay for later maintenance and often pay for utility pipes, arterial roads, and other amenities years in advance of actual development. If the development never takes place and the developer goes bankrupt, cities and counties may be faced with massive debt that yields no return, so they must reduce spending on other services to repay it.

From a macroeconomic standpoint, there is no difference between public and private borrowing and the resulting debt overhang. In both cases, the investment in fixed capital, particularly in cases where repayment stops or is delayed, creates a severe drag on the economy because productive enterprises are starved for financing for several years. That is why so many small businesses face bankruptcy in the early stages of economic contraction.

Overextended Banks

The final element in the real assets theory of economic crisis is the process by which banks become overextended and highly leveraged. Banks are the public face of economic crises because their lending behaviour during a boom adds fuel to the fire and their foreclosure on borrowers during the contraction phase adds to the drama that makes them seem like the villains.

Banks are always heavily leveraged, meaning their reserves are a small percent of their loans. Leverage enables banks to profit during boom periods because the value of their assets seems to be rising in the form of the real estate they hold as collateral. But eventually, the price of real estate reaches a peak and begins to fall. At that point, the value of bank assets is put in danger. Everyone tries to sell their real estate at the same time, but that just drives the price down further. When borrowers cannot repay their loans or choose to abandon property that is “under water” (worth less than the loan on it), the bank takes the property that was held as collateral. Now banks have a lot of low valued property that they cannot sell. Their reserves become tied to these illiquid (unsellable) assets, so they can no longer lend money to small businesses for their operational expenses. As a result, bankruptcies rise dramatically.

The price of land could not rise during a speculative binge unless banks and other financial intermediaries were willing to lend money against inflated collateral values. Bankers thus contribute to the speculative process by expanding their balance sheets and knowingly leveraging their assets beyond the bounds of good business practice, sometimes to the point of criminality. Creating subprime mortgages and lending money to families that banks knew would not be able to repay their loans was not an innovation in the 2000s. The same policy was put into practice during the 1920s, but it was called “shoestring financing” then. In addition, lobbyists for the banking industry persuaded the U.S. Congress to overturn the Glass-Steagal Act, which was adopted during the Great Depression to separate commercial and investment banking. Enabling the same banks to perform both operations permitted them to turn normal mortgages into collateralised mortgage obligations, through which they cut up mortgages of various levels of risk and repackaged them for sale as investment instruments. When land prices dropped, and those assets fell far below their face value (thereby becoming “toxic”), it was nearly impossible to hold mortgage lenders accountable for their irresponsible lending.

Although a few investment bankers profited handsomely by putting the global economy at risk, other banks such as Lehman Brothers gambled and lost. Many commercial banks that participated in the euphoria of making money from rising land values also created the conditions of their own illiquidity. For the year ending June 1, 2010, Goldman Sachs showed a 24.5 percent return on equity, but during the same period, the return for all banks was only 3.5 percent, far below the S&P average of 14.5 percent (Reuters 2010). By 2014, when the return for all banks had risen to 10.2 percent, the five-year average for banks was 4.7 percent, suggesting a very slow recovery in the banking sector (Reuters 2014). Even those figures exaggerate the health of banks in the wake of the crisis. If banks were required to “mark to market” (assign current market value to their real estate assets), large numbers of seemingly healthy banks would have been bankrupt in 2010, meaning their liabilities would have exceeded their assets and their equity would have been negative.

In summary, the real-assets theory of crisis views the disorganised activities of land speculators and the organized activities of ambitious bankers as equal partners in fomenting the cycle of boom and bust. They work in tandem to freeze capital in forms that take years to thaw, thereby undermining the flexibility of the economy and the banking system at the same time.

Comparative History

We now have the outline of a real-assets theory of economic crisis that can explain major periods of expansion and contraction in any economy in which land is exchanged through impersonal, monetised markets. Feudal and modern socialist command economies lack that characteristic. Thus, the model predicts that, whereas they may have suffered low productivity and short-term business cycle problems due to production bottlenecks, they should not have experienced the sorts of dramatic swings to which modern market economies are subject.

Market economies have, however, experienced cycles of boom and bust for centuries. In the United States, peaks occurred in 1797, 1817, 1836, 1857, 1872, 1893, 1909, 1928, 1957, 1973, 1989, and 2006. There are individual studies of a number of these panics, although few economists have noted that they have common characteristics and occur with regularity every generation. As Carmen M. Reinhart (2010) has noted: “The economics profession has an unfortunate tendency to view recent experience in the narrow window provided by standard datasets. With a few notable exceptions, cross-country empirical studies of financial crises typically begin in 1980 and are limited in other important respects. Yet an event that is rare in a three-decade span may not be all that rare when placed in a broader context.” The “South Sea Bubble” of 1720 is well known. Before that was the Dutch “Tulip Bubble.” One French historian has documented cycles as far back as the 12th century (Levasseur 1893).

One piece of evidence of a common pattern has already been presented: the similarity of the successive rise and fall of home building and nonresidential construction, approximately two to three years apart. For the United States, there is some statistical evidence that that pattern can be traced further into the past, although the data become murkier the further back we go. In the decades before the Great Depression, the peaks in the value of housing construction occurred in 1892 and 1909, in each case followed by a drop of more than 20 percent in the following year. In 1892, the peak in residential and nonresidential construction coincided, whereas in 1909, the nonresidential peak followed by one year, in 1910 (U.S. Census Bureau 1975b: Columns 73, 75). This confirms the real-assets theory, but it raises doubts about the generality of the pattern by which nonresidential peak construction occurs two or three years after the peak in residential construction. A theoretical explanation for this variation is called for, but we offer none here. This is another area for further study.

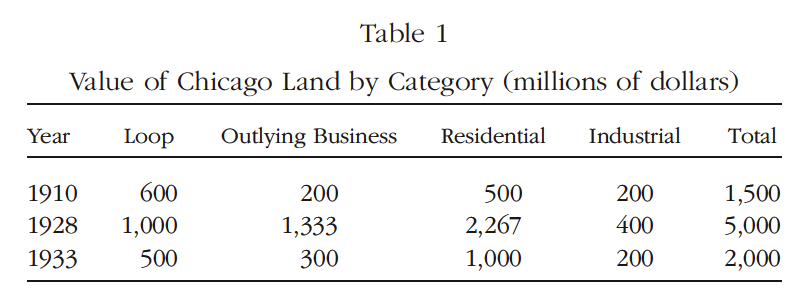

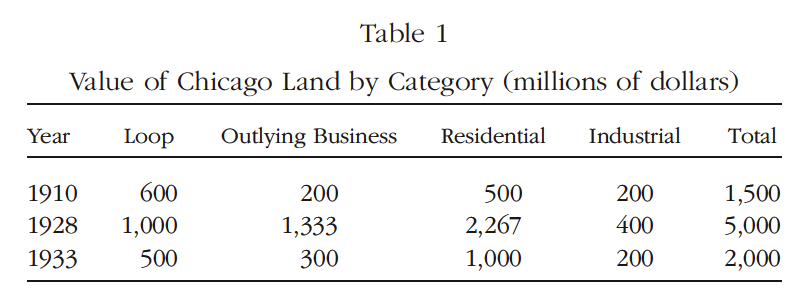

Hoyt (1933) offers further empirical evidence that land values peak immediately prior to major depressions, and he extends this analysis back to 1835. He does this by focusing on a single city: Chicago. In this case study, he was able to gather data on actual land values rather than having to rely on proxies such as the value of construction. Hoyt (1933: 348) shows land value peaks in 1836, 1856, 1872, 1891, and 1928, followed by a decline in land prices of at least 50 percent in all but one case (1872), when prices fell “only” 33 percent.

In addition to confirming the general hypothesis that land value peaks precede depressions, Hoyt (1933: 347) also reveals the differential pattern within a city. Table 1 shows the value of land in Chicago in 1910, 1928, and 1933 according to usage categories: the Loop (central business district), outlying business districts, residential, industrial, and total (citywide average). The data clearly show that land values shift to more peripheral locations during boom periods and contract more severely in those same areas after a crash. Thus, land values in the central business district did not even double from 1910 to 1928, but land for housing and outlying business districts grew by a factor of 4.5 and 6.7, respectively. The subsequent crash was also much greater in outlying areas. This shows that the volatility of land prices is in newly-developedmarginal lands.

The central business district contained only 0.1 percent of the land in Chicago’s borders in 1933, and yet it held at least 20 percent of the city’s land value during most of its first century of expansion. The percentage fell during boom periods, when the bubble in land values in outlying areas took place, but it rose during periods of recovery when peripheral land values fell faster and further than inner-ring land values did. (Simpson and Burton (1931) elaborated on this phenomenon and provided one inspiration for Hoyt’s work.)

In England, for example, between 1892 and 1926, the average price per acre of residential land rose from £130 in the first four years to £950 in the following period, fell again to £130 in the next five-year period, rose to an average of £400 for five years, and finally fell to £210, £150, and £140, in the final three periods of seven, five, and five years, respectively (Harrison 1983: 95, citing Vallis 1972: 1209, Table II).

The experience of other nations also fits the pattern. In the 1990s, Mexico, Chile, Thailand, and Malaysia experienced economic crises that were reported to have been caused by rapid influxes of “hotmoney” that drove up prices, followed by equally sudden withdrawals of cash that left their economies short of credit and unable to pay debts. Most of the analysis in English about these crises was conducted by economists who were trained in international economics, and who apply financial analysis to every economic problem. In effect, they were trained to pay attention to monetary flows and to ignore the effects of changes in land values. One searches in vain to find more than a passing reference to land values in their discussions of those crises.

Felix (1987) offers a refreshing exception to that rule. Analyzing the Baring Crisis in Argentina in 1890, he makes clear that the problem was not one of financial impropriety but rather a process of growing expectations of cashing in on growing land values, with no end in sight. Felix (1987: 8) describes the situation as it unfolded:

The 1880s boom was deeply marred by . . . the inability of markets to signal

accurately the limits of [the extension of capital over the landscape and by]

. . . project promoters and security brokers, who [could] gull outsiders into

continuing to feed the boom in asset values.. . . Railroad trackage rose from

twenty-eight hundred miles in 1885 to seventy-two hundred miles in 1891,

with thousands of additional miles under construction when the debt crisis

exploded, yet freight tonnage rose only 28 percent.

In short, this was a crisis created by premature investment in marginal assets based on false expectations about the capacity of those assets to yield revenue.

Another exception to the practice of ignoring the significance of land bubbles is a paper by Gabriel Palma on regional economic crises in the 1990s. Although his paper is on the need for capital controls to prevent externally-driven rapid fluctuations in a nation’s money supply, he provides detailed evidence of a connection between real estate bubbles and subsequent economic collapse in Chile, Mexico, and Malaysia. In Mexico, Palma (2000: 19, 21) indicates that land prices rose 600 percent before the 1994 crisis, and residential construction doubled in five years, while investments in machinery, equipment, and infrastructure were cut in half. In Chile, a real estate price index rose by a factor of 10 in six years, and in Malaysia, real estate prices jumped by a factor of 5.5 from 1992 to 1997 (Palma 2000: 41, 47–48). When land prices came down in each country, banks were left with nonperforming loans on property they acquired through defaults. Nevertheless, this source of economic instability is less visible than the international investments that first financed the bubbles and then were withdrawn when trouble came. Since similar troubles have occurred where capital flows are more domestic than international (in the United States, for example), it is dubious to blame the crisis on peculiarities of international flows. The underlying problem is the land market itself.

The same is true of the most recent economic crisis. It is interesting to look at the countries where there was a rapid increase in land prices (using housing prices as a proxy) during the years before 2008. According to Montagu-Pollock (2014), the following jurisdictions experienced growth of housing prices of at least 100 percent during the decade before 2008 or a comparable increase over a longer period: Denmark (>200% from 1993 to 2007), Finland (100% from 1997 to 2008), Paris, France (160% from 1998 to 2008), Greece (225% from 1993 to 2007), Hong Kong (175%), Indonesia (100% from 2000 to 2008), Ireland (320% from 1996 to 2007), Italy (100%), Norway (240% from 1994 to 2007), Serbia (300%), Singapore (40%), Slovak Republic (100%), Slovenia (100%), Spain (100%), Sweden (150% from 1998 to 2008), Ukraine (140%), and the United States (100% from 1996 to 2006).

It is interesting to note that Spain, Greece, and Ireland, the threecountries that suffered the most severe crises in the Eurozone, are onthe list. They reveal how falling land prices can affect the entire economy by both slowing down the construction sector and by tying up bank loans with toxic real estate. According to Eurostat (2014a), Ireland’s house prices were cut in half between 2007 and 2013, Spain’s fell 37 percent from the first quarter of 2008 to the second quarter of 2014, while Greece’s prices remained stable, which strongly suggests that the data in this Eurostat table are incorrect. As a result, the value of building construction fell by 73 percent in Ireland (2008–2011) and 77 percent in Spain (2007–2013). This table has no data for Greece, which will be addressed below.

In Spain, Stucklin (2012) points out that planning approvals for new home developments are down 93 percent compared to the 2006 peak. 340 The American Journal of Economics and Sociology Just as Hoyt (1933) found the greatest land price volatility in outlying areas of Chicago, Harris (2013) summarizes a Spanish Ministry of Development report that indicates land prices fell furthest along the northern coast of Spain and in villages of less than 1,000 people.

Since the widely-discussed economic woes of Greece were attributed entirely to its large public deficit for several years after 2009, let us examine the evidence more closely to determine if land price changes (boom and bust) were indeed a major factor in its ongoing crisis. Koo (2012: 8), citing Bank of Greece data, observes that house prices in Greece rose by a factor of 1.6 (from 100 to 260 on a house-price index) from 1997 to 2008. The Bank of Greece (2014: Table II.7) shows apartment prices in various cities in Greece falling by around 30–35 percent from 2008 to 2013. In addition, building construction in Greece fell by 86 percent from 2007 to 2013 in Greece (calculated from Eurostat 2014c). The spiraling downward of the Greek economy in the wake of this crisis has left 27 percent unemployment. These are precisely the sorts of statistics of rising and falling land prices (via proxies) that one would expect if the crisis was precipitated by land speculation. Of course, the severity of the crisis in Greece was compounded by its fiscal deficit, but the structural weakening of the economy was a product of land market volatility. Sampaniotis (2011: 27), an analyst at Eurobank Ergasias, is simply mistaken when he concludes: “The real estate market was not a problem in Greece.”

Malzubris (2008) and other analysts of Ireland’s housing boom have generally agreed that the Irish economic crisis was due primarily to the increase in housing prices from 1996 to 2006, and the subsequent crash. The experience of Ireland was extreme: house prices rose more than four-fold (314 percent) in a decade (Economic and Social Research Institute 2011). Irish banks now hold 95,000 home mortgages that have been nonperforming for at least 90 days; they constitute almost 12 percent of all mortgages in Ireland (Phillips 2013; Castle 2013). Even if the banks foreclosed (which Irish law has effectively prevented), the banks would gain little: most of the bad loans would simply become toxic assets in the banks’ portfolios. That would not help the banks with their very low capital ratios (equity/asset ratios). With their cash tied up in housing capital that is not turning over (being repaid), Ireland faces a serious, long-term liquidity crisis of the sort that Japan has lived with ever since its land boom came to an end in 1990. Bailout loans have avoided a complete economic collapse in Ireland, but they have only delayed the reckoning.

We have emphasized here only the most recent examples of how thespeculative growth and decline of land prices affects economic performance. The data for fully testing the real-assets model of economic instability are almost nonexistent because governments tend to collect data only if there is a model that requires it. (For that reason, the Keynesian model, which requires estimates of aggregate demand and supply, could only be tested after World War II, when governments began collecting the necessary data.) A handful of governments recently began collecting aggregate national information on housing prices, but only a few collect data on land prices. As we have seen from Hoyt’s intensive examination of Chicago, the data should also distinguish between land prices in the central business district and in outlying areas, and between commercial and residential districts. Further refinements of the real-assets model may reveal other distinctions that would improve its predictive power. For the time, it seems we must remain content to accept data on housing prices that combine land and building prices andmask the differences in the rate and direction of change of each element.

The Case of China

China presents an unusual opportunity for testing the real-assets model of macroeconomic instability because it has not yet experienced a full-blown bubble followed by a crash. Nevertheless, as I write this in the fall of 2014, the Chinese economy appears to be entering a period of economic contraction, with investment capital drying up and ceasing to finance the kinds of projects that have been the engine of growth in China for several decades. Those who regard every major economic event as unique and caused by random external factors will regard as coincidental any features in common between China’s current experience and the retrenchment of the U.S., Irish, Spanish, and Greek economies since 2008, but the real-assets model predicts the same pattern will be found. There are, of course, differences. Whereas privately owned banks and private capital investment are the norm in the United States and Europe, the primary source of investment capital in China has come from state-owned banks. In addition, all land is owned by the state in China, in contrast to most other countries, where individuals and businesses own land in fee simple. Nevertheless, de facto private ownership of land occurs in China through 70-year leases for residences and 50-year leases for most commercial purposes. As a result, the economic fundamentals are the same, and those characteristics are likely to supersede the differences.

The most notable resemblance between China and crisis-afflicted Western nations in relation to macroeconomic instability is the rapid increase in land prices over a period of five or more years. Gyourko et al. (2010: Figure 5) have estimated that land prices in Beijing rose more than 750 percent from 2003 to 2010, but they are hesitant to regard that as a price bubble, absent more complete knowledge about China’s property markets over a longer period. (By contrast, average housing prices in 35 cities rose only 100 percent during the same period (Gyourko et al. 2010: Figure 1). This reveals the much higher volatility of land prices than housing prices, as one would expect.)

Gyourko et al. (2010) and other analysts present other evidence that a land-price bubble had begun to form in China by 2007. For example, Gyourko et al. (2010: Figure 3) shows a price-to-rent ratio in eight major cities, in which the mid-point of the eight cities was around 30 from 2007 to 2010. (Previous years are not available and thus historic trends cannot be observed because data were not collected before 2007.) By comparison, Davis et al. (2008) show the price-to-rent ratio in the United States rose to 30 only from 2005 to 2007, just before the bubble burst. However, this information is not decisive, since the price-rent and price-income ratios have only limited predictive ability in forecasting price peaks and declines. Until there is evidence that they predict over-investment in fixed capital, they function only as secondary indicators of a price bubble.

Another sign of a reversal in the housing market that will lead to a general economic contraction in China is the buildup of housing inventories. Nie and Cao (2014: 3) report this accumulation in the past two years in China: “The average inventory-to-sales ratio—a measure of how many months it would take to sell all existing inventory at the current rate of sales—rose 50 percent in the past 12 months, from 12 months in June 2013 to 18 months in June 2014, a rate well above the United States’ 5.8 months.” Nie and Cao (2014: 1) also point out that investment in private housing in China has grown an average of 20.2 percent per year since 1998, double the rate of GDP growth, and it now comprises 15 percent of GDP. Thus, a decline in housing construction, almost certain, given the excessive inventory buildup, will have a large and immediate effect on the overall growth of the Chinese economy.

We should have learned from earlier boom-bust cycles that the seeds of bank failure may be sown in a small number of jurisdictions. Those jurisdictions are often not the largest cities. Thus, national averages of land prices, house prices, and inventories, and statistics about prices in the largest cities may not accurately warn of an impending crash, which may come from the hinterlands. China is now famous for its “ghost cities,” massive investments in land and infrastructure that stand virtually idle, but since there are only a handful of them, they are statistically unimportant by themselves. Far more relevant are the thousands of small, underutilized development projects, scattered in hundreds of small cities and towns. Davis and Fung (2014) summarize the situation in the large number of small- and medium-sized cities, which is precisely where trouble has been brewing.

Evidence is mounting that in dozens of third- and fourth-tier Chinese cities rarely visited by foreigners, overbuilding is out of control and a major property-market slowdown is now under way. The 200 or so Chinese cities with populations ranging from 500,000 to several million account for 70% of the country’s residential-property sales. In many of these cities, developers are slashing prices and offering freebies such as kitchen furnishings and parking spaces as they try to work through vast gluts of unsold property. Protests are breaking out among buyers angry that their investments are losing value.

Overbuilding in small cities throughout China is a much better indicator of a coming decline in land prices and loss of bank liquidity than indices that measure only the big cities. Of course, if the building boom in Beijing, Shanghai, and Hangzhou occurs on the margins of those cities, then their condition could contribute to a major economic reversal. However, since no existing construction or price index reveals the location of construction, that aspect of the process will remain hidden until after the crash occurs, and the location of abandoned projects in major cities becomes apparent. While bad investments in the center ofa city may eventually be recovered, investments on the periphery will normally be lost forever.

It would also be desirable to know much more about the commercialreal estate building boom and its impending collapse. As early as 2010,office towers were facing vacancy rates of 15–17 percent in Beijing and 13 percent in Shanghai (Colliers International 2010). That was viewed as mildly alarming at the time. It has now become clear that the problem of excessive expansion in real estate is a national problem, particularly in the mid-size cities. Frank Chen, executive director for China of CBRE, explains that the vacancy rate in second-tier cities is 21 percent, double the rate considered healthy (China Economic Review 2014). FlorCruz (2014) cites an example of this phenomenon: “Chengdu, in the southwestern province of Sichuan, embodies the problem faced by many Chinese cities—a huge oversupply of buildings spurred by abundant finance. Nearly half the offices in the city are now vacant, and the problem is expected to worsen: More than 1.5 million square meters of space are scheduled to be completed this year.”

As if the rise of land values and excessive construction of housing and commercial units were not enough, local governments in China have also been borrowing heavily and guaranteeing loans, all to engage in real estate developments of various kinds: to buy land or make infrastructure improvements. According to Davis and McMahon (2013), local government debt grew from 10.7 trillion yuan in 2010 to 17.9 trillion yuan ($3 trillion) in 2013, and only a small portion of the increase has come from conventional banks. More than 10 percent of financing now comes from “shadow banks” and about 17 percent comes from “other” sources. The transition from conventional sources of capital represents a decline in the quality of the investments. Davis and McMahon (2013) continue:

China’s world-beating record of about 10% annual growth for the past three decades is based in large part on local governments spending heavily on such building projects. But since the global financial crisis of 2008, that construction has depended more and more on heavy borrowing and often resulted in dead-end projects that have a tough time paying their bills, economists say. Nearly half of the debt comes due by the end of 2014.

The reference to “dead-end projects” is a good indicator of the falling quality of local government investments. It points toward the problems that arise when marginal sites are being developed during a boom, locations that cannot generate enough revenue to repay loans.

As Das (2014) explains, 90 percent of bank loans since 2008 were invested in fixed assets, particularly by state-owned enterprises. The result has been a total debt held by government, corporations, and households of around 200–250 percent of GDP. Local government debt is around 25 percent of the total, and its share of the total has increased substantially since 2008. But, Das continues, official debt statistics do not include various off-budget forms of debt, such as “nonperforming loans purchased from state-owned commercial banks, which all trade on the basis of an explicit or implicit government support.” Thus, it is difficult to know the true debt situation in China today. This somewhat parallels the condition of today’s Euro-zone, where major banks depend on presumed government support, while the supporting governments depend on the banks.

Many commentators in the past few years have discussed the ballooninginvestment by the Chinese government and rising debt levels.For example, gross capital formation in China was 49 percent of GDP in 2013, more than double the world average (World Bank 2014). But the quality of debt is at least as important as the quantity. According to Das (2014):

Chinese data measures two different types of investment—gross fixed capital formation measures investment in new physical assets which contribute to GDP and fixed-asset investment measures spending on already existing assets including land. In 2008, gross fixed capital formation and fixed interest investment were roughly equal. Today, gross fixed capital formation has fallen to about 70% of fixed-asset investment, consistent with increasing turnover of already existing assets at frequently rising prices. Investment in new assets is heavily focused on frequently large scale infrastructure and property. The major concern is that many of the projects will not generate sufficient income to service or repay the borrowing used to finance the investment. (Italics added.)

Since land is the primary existing fixed asset in which investment occurs without adding value, this evidence confirms that the Chinese economy is now being weakened by excessive investment in a land boom.

Riddell (2014) makes the same point, although more obliquely. He notes that China’s nominal growth rate has slowed from an average of 10 percent per year to 7.7 percent in 2013. At the same time, the rate of investment has increased from 48 percent of GDP to 54 percent. Logically, he suggests, this is a sign of danger. If investment is increasing and being used productively, GDP should be rising in step with the new capital. However, if the growth rate of GDP falls as investment increases, that indicates investments are either sterile or not adding as much value as before. Riddell (2014) continues:

It should be a concern if a country experiences a surge in its investment rate over a number of years, but has little or no accompanying improvement in its GDP growth rate. . .. This suggests that the investment surge is not productive, and if accompanied by a credit bubble (as is often the case), then the banking sector is at risk (e.g. Ireland and Croatia followed this pattern pre 2008, Indonesia pre 1997). . . . The most likely explanation for China’s surging investment being coupled with a weaker growth rate is that China is experiencing a major decline in capital efficiency.

Whatmight cause a “credit bubble” or a “decline in capital efficiency”? In the absence of any reference to real estate or other real assets, presumably Riddell, like most other analysts, would assign responsibility to the banking system.

A more plausible explanation, and one that fits the real-assets model presented in this article, is that the bubble and decline in capital efficiency are the result of speculative investment in land, particularly marginal land, and in complementary fixed capital, which will lose much or all of its value after a crash. Before the economy becomes frozen, these investments are counted as contributions to growth, but eventually they will turn out to be sterile because they actually drain value from the economy rather than adding to it. At that point, the previous growth will be revealed as a mirage. The problem is thus not the total quantity of debt per se, which is positive as long as it is productive and self liquidating. The threat posed by debt to the national economy arises only when it fails to turn over with enough frequency and engage with labor in producing needed goods and services. The total quantity of debt is relevant only because high levels and high growth rates of debt generally indicate investment inmarginal land and capital projects.

Despite all of the signs that the days of China’s miraculous growth are coming to an end, opinion remains divided about whether it is facing a crisis similar to the one experienced by the United States and Europe in 2008. Leeb (2013), still bullish on China in July 2013, wrote: “Whatever overbuilding China may have done, it was simply insufficient to create an economic crisis. The IMF authored the most comprehensive report to date on Chinese overinvestment. China’s debts, unlike those of the U.S. and most other countries, the IMF notes, are owed to China itself. Therefore, the risks of a full-blown Chinese economic crisis remain small. . .. [F]ears of a Chinese real estate bubble in particular are way overblown.”

Nevertheless, the “overblown” bubble seems to be starting to burst. CNTV (2014) reports a 7.6 percent decline (annualized basis) in house prices from January to July 2014 in 70 Chinese cities. Anderlini (2014), writing in the Financial Times, announced that the March 2014 default of Zhejiang Xingrun Real Estate Company, a Chinese developer, prompted an emergency discussion with China Construction Bank, its largest lender, and the central bank of China about a potential bailout. Zhiwei Zhang, an economist at Nomura Securities, added that most financial analysts had not yet taken account of the growing risk of such defaults because they were misled by rising land prices in big cities, even as property values had dropped by as much as one-third in some provincial areas, which accounted for two-thirds of the housing under construction in 2013.

The Chinese government sought in January 2014 to slow the boom in property prices by limiting credit (Kerkhoff 2014). By September, it had reversed course and was trying to prop up the sagging housing market with incentives for first-time home buyers (Qing and Shao 2014). But the government is learning the limits of its power to control markets with short-term financial instruments. Even though the government owns all of the banks in China, it will not be able to stem the tide of defaults in a falling land market because it can do nothing to transform fixed capital, tied up in real estate, into productive circulating capital.

The real-assets model thus predicts that China will face a significant decline in growth rates over the next three to five years, possibly dropping into the realm of negative growth. Unemployment will rise, and conventional stimulus techniques will fail to revive the economy. Land and other asset prices will fall, and if the Chinese banks mark them to market, they will face liquidity problems in the short run. If they fail to revalue assets and keep them on their books according to their historic highs, as Western banks have generally done, it will take even longer to recover because banks will only be able to resume normal lending when land prices rise enough to reach the levels of 2013.

Policy Responses

We have now seen evidence from a number of countries that a real assets theory can account for a number of past and present economic crises that have otherwise been attributed solely to financial mismanagement. By integrating real variables into the model (investments in land and fixed capital compared to circulating capital, and the geographic location of investment), policymakers have more options to use in formulating instruments to prevent asset bubbles and financial crises.

Post-Crash Response

The current orthodoxy about economic crises is that each one is peculiar and that it is therefore impossible to model them or create policies to prevent them. Each is caused by a sudden change brought about by external forces, an “exogenous shock,” such as a sudden increase in oil prices, the default of a major bank, or the rapid withdrawal of capital from a nation’s banking system. In such a world of random cataclysm, all one can do is to make an effort to stabilise the economy after a shock with fiscal and monetary policies. The debate is then mostly limited to a conflict between the call for austerity and the call for stimulus.

Even within the framework of this orthodox account of randomly generated crises, there is one policy that could be implemented. After a crash has occurred, one simple response that would restore an economy to normalcy in short order would be to require all banks to value their assets at current market value. Banks that lent wisely instead of joining the mob mentality at the height of the boom would have nothing to fear. By contrast, banks that supplied land speculators with credit would face bankruptcy, and equity holders would lose their investment in the bank. This policy need not weaken the banking system as long as the central bank provided enough equity on an emergency basis to keep the bank operating until private investors could be sure the toxic assets had been removed and were again willing to buy the government’s shares. This policy of requiring honesty in accounting could have the effect of deterring banks in the future from financing asset values not merited by normal lending practices. However, since many of the largest banks are now “too big to fail,” meaning too big to be held accountable, it is not clear whether this remedy could actually be applied.

Crash Prevention: Using the Real-Assets Model

The real assets model proposes two possible methods of preventing panics before they ever have a chance to get started. The first method involves credit controls. The second method involves real-asset price limits.

Credit controls

The original impetus behind periodic booms and busts in modern economies is the desire to gain a profit by investing in an activity that

generates economic rent—money for nothing. As a collective frenzy builds, banks become involved and accommodate the boom with lending against properties with inflated value. As a result, it seems to many analysts that the best way to prevent or control the boom is to limit credit.

On its face, increasing interest rates, capital requirements, down payment requirements, or any number of other rules ought to be capable of regulating aggregate financial transactions and preventing speculative booms from occurring. In practice, however, most such efforts ultimately fail. When land prices start rising, lenders in booming cities or regions become more resourceful in finding ways to circumvent regulations, sometimes legally, sometimes not. This does not mean that financial regulations can be ignored. It means that other instruments must also be pursued.

One conclusion that has been derived from the series of economic crises in developing nations is that they should protect themselves from boom and panics by instituting capital controls—rules that limit the amount of money that can be invested from outside the country.

Logically, this makes a great deal of sense. Palma’s (2000) analysis of crises in Chile, Mexico, and Malaysia in the late 1990s indicates that their economies were destabilized by a rapid influx of capital, followed by a sudden decline a few years later. In a relatively small economy, only a small amount of mobile capital can cause instability. The model Palma uses, however, presupposes that the boom in asset prices in those countries was caused by the influx of capital.

Kim and Yang (2008) investigated the validity of that assumption and discovered that although capital inflows in emerging Asian economies contribute to booms in asset prices, they only explain a small part of asset price fluctuations. Kim and Yang (2008: 18) conclude: “Capital inflows indeed contributed to asset price appreciation in the region, although capital inflow shocks explain a relatively small part of asset price fluctuations. Positive capital flow shocks increase stock prices immediately and land prices with some delay.” One might assume, nevertheless, that capital controls can help regulate boom-bust cycles in small, open economies. Olaberrıa (2012:18) finds just the opposite: “A perhaps surprising result is that higher capital controls (less financial openness) do not appear to reduce the probability of large capital inflows being associated with booms in real asset prices.”

Consider also the anomaly that exchange controls in central Europe, early in the 1930s, were focused on blocking capital exports, not imports (Ellis 1941).

Again, the conclusion from recent evidence seems to be that regulatory controls can only be partially successful in preventing the sorts of asset price fluctuations (booms and busts) that destabilise market economies. If the instability of developing economies comes primarily from factors internal to those economies, attention should be focused on getting the fundamentals right.

Since the major economic disruptions of Mexico and Malaysia are surprisingly similar to the periodic crises that have affected Japan, the United States, China, and Spain, it would seem that “the fundamentals” are universal, not limited to economies that require financial “deepening.”

Taxing land values to limit asset prices

Although adopting financial regulations that limit the credit that banks can issue during a boom may help prevent future economic crises, it is not a sufficient solution. The problem lies mainly in implementing the restrictive rules adopted after a previous crash and enforcing them when rising incomes precipitate the next round of growing asset values. Bank regulators who try to enforce such rules during a boom are trying to fight psychological forces that deem the rise of asset values as “progress.”

A second approach is also needed to contain the problem at an early stage, before asset prices rise fast enough to create the collective frenzy that becomes difficult to control. The required instrument would reduce the incentive of borrowers to invest in fixed assets. A substantial tax on the value of those assets, particularly on land values, would lower the price at which those assets trade and simultaneously raise holding costs. At present, a borrower who can borrow $1 million with a $100,000 down payment must pay carrying costs (interest) on $900,000, a fixed amount for the life of the loan. By contrast, if the price of land is subject to a heavy tax, the carrying costs are divided between interest and tax payments. If tax assessments are updated frequently in a rising market, the part of the holding cost associated with the tax will rise with the price and send a signal to buyers discouraging them from purchasing land for speculative purposes. With that simple device, it should be possible to prevent the growth of asset values (particularly land values) beyond their productive capacity. What gives rise to a boom is the idea that a purchase can be quickly sold to another person who also expects the rapid escalation of prices. A tax, backed by frequent reassessments, automatically tempers and dampens that process. When fee-appraisers base their valuations on “comparable sales,” overpricing of each parcel generates a cumulative reflective process wherein overpricing may reflect or reverberate back and forth (Gaffney 1986). When a tax assessor follows an upswing in comparable sales it has the opposite effect. I am not aware that this important tempering function of land value taxes as been recognized either in the literature or in the consciousness and practice of market actors.

The effectiveness of the use of property taxation as a method of limiting speculation has implicitly been demonstrated to some extent in the United States. A number of states have adopted legislation that limits the rate of increase in the assessed value on residences. California began the process in 1978 by limiting additions to assessed value for property tax purposes to no more than 2 percent per year. Similar laws were subsequently adopted in Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Iowa, Maryland, Michigan, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Carolina, Texas, and Washington (Mikhailov and Kolman 2002). In the subsequent economic crisis, the eight states that led the nation in foreclosures (Nevada, California, Arizona, Florida, Oregon, Illinois, Georgia, and Michigan) all had assessment limitations. Legislation that was intended to protect homeowners had the unintended effect of permitting higher land prices and greater land speculation because assessments could not keep up with rising prices and thus temper the “irrational exuberance.”

In nations where provinces or states control the assessment and taxation of land, the disruptive character of land speculation is beyond the reach of the central government. In China, that is not the case. In principle, at least, the central government can implement a land value tax or property tax that would limit investment in land for speculative purposes. Thus, it is significant that the leadership of China, alone among nations, has explicitly stated the intention of adopting a property tax as a method of controlling speculation in housing prices. Xinhua News Service (2006) reported that a prominent economist, Lin Yifu, director of the China Economy Research Center of the Beijing University, favored a property tax “to rein in speculative investment and ward off a possible financial crisis.” Four years later, “a report submitted to Deputy Premier Li Keqiang said surging prices for housing price posed a threat to social stability” (Tao 2010). Presumably, the news was not that a report was written, but that Deputy Premier Li had accepted it. Li Keqiang, a trained economist, became Premier of China in March 2013 (the number two position in the government). That same month, the government announced a plan “to introduce a unified national property registration system by the end of 2014, which could eventually make it possible to impose an annual property tax on households—yet another way the authorities expect to fight housing speculation and fend off bubbles” (Barboza 2013). In the second half of 2014, as the crisis began to unfold, and house prices beganto fall in most of China, top officials remained quiet (Lelyveld 2014). It seems likely that top government officials are aware that China’s banks will soon face a liquidity problem, but a property tax and other preventive measures that might have prevented a rise in housing prices can no longer avoid a crisis.

Conclusion

One of the most basic principles of economic theory is that it deals with real costs: the time, energy, and materials we give up in one pursuit to follow another. In that sense, money is not real. It is just a symbol. There is no real cost when we spend money. In the same way, money, by itself, does not represent the creation of value. It merely serves as a claim on value that is created by real economic activity.

A great deal of economic analysis in recent decades has created confusion on this basic point. It treats money as an object of analysis as if the manipulation of symbols is the same as the management of real relationships. For example, the standard Keynesian identity that equates GDP with consumption plus investment plus government spending plus net exports creates the illusion that we can remain indifferent about the qualitative features of each variable. Macroeconomics, in this view, is simply a matter of balance sheets and has nothing to do with the real productivity of private or public investments. In this world of magical thinking, a dollar spent on education is the same whether students gain any proficiency or not.

The two most important features of a real-assets model are 1) that the real economy matters, and 2) that the health of an economy depends on the quality, as well as the quantity, of investments. Those who claim that banks can expand their balance sheets arbitrarily and without adding deposits are correct. But in doing so, banks destabilize the financial system by increasing their leverage—lowering the ratio of equity to assets. If they are simultaneously reducing their liquidity by investing heavily in fixed capital (long-repayment projects) rather than circulating capital (short-repayment projects), they are pushing the entire economy into a hazardous position.

The real-assets model explains why economic crises have been a.recurrent feature of capitalist economies for the past two centuries and more. The French historian Pierre Emile Levasseur (1893) traced cycles back to 1200 A.D. The problem is not inherent in the private ownership of capital, the characteristic feature of capitalism. The systemic flaw lies in the failure to ensure that investment is balanced between circulating capital and fixed capital. The greatest crises arise when land is not taxed adequately to prevent the speculative growth of its value. Land speculation then leads periodically to over investment in complementary fixed capital, often in peripheral areas of low inherent value. Credit becomes tied up in long-term investments, many of which eventually default. The resulting foreclosures leave banks with overvalued assets that they refuse to mark to market, leaving banks unable to generate new credit during the lengthy recovery.

For a number of years, it seemed that the Chinesemiracle of rapid economic growth based on massive public investment would somehow steer clear of the economic distress caused by land speculation and marginal investment in capital projects. Because of the backlog of latent demand in that economy for better housing, it was possible to construct thousands of projects in mid-size cities without exhausting the ability of China to make efficient use of those investments. By 2014, however, it became clear that China’s economy had reached a limit of productive investment in housing and other fixed investment and would be subject to the same constraints as other economies. There were voices in China that began warning of this fate as early as 2006, but they were ignored. It now seems likely that China will face several years of sluggish growth as land prices fall, defaults rise on marginal projects, and the loss of liquidity of the state-owned banks forces the central government to cut back on its investments. At the same time, as house prices fall in the major cities, the urban middle class will respond to its reduced nominal wealth by cutting back on consumption. The combination of these effects will reduce growth further and increase the rate of unemployment.

The one ray of hope in this otherwise gloomy picture is that some of the top leadership of China is at least aware that rising land prices need to be controlled by means of taxation. This is the first sign that any national government has recognized the use of land value taxation as an instrument of macroeconomic policy. Although that recognition came too late to prevent the present crisis in China, it could be used to prevent future repetitions of the present situation. If China can learn that lesson in its first experience with a boom-bust cycle in land values, it will be far ahead of Western governments that have ignored the signs for centuries.

Notes

1. There is no index of land prices in the United States to show this. There are, however, many studies of particular times and places and industries that show the point clearly enough to be sure of it. We discuss one of them below: Homer Hoyt’s classic 100 Years of Land Values in Chicago, 1833–1933. Many others are in the bibliography.

2. All construction figures from 2002 to 2012 come from U.S. Census Bureau (2014a). The 2000 estimate of housing construction comes from U.S. Census Bureau (2012). All monthly figures represent seasonally adjusted annual rate.

3. If capital is $5 million, the annual payments at 8 percent will be $419,300. Total payments will be $16.77 million (40 x $419,300). Of that amount, $5 million repays the principal, and $11.77 million is interest, which is 70 percent of the total payment.

References

Anderlini, Jamil. (2014). “China’s Central Bank Holds Bailout Talks with Property Developer.” Financial Times. March 18. http://www.ft.com/ cms/s/0/e5590566-ae6c-11e3-aaa6-00144feab7de.html#axzz3KI8iq9PX

Bank of Greece. (2014). “New Index of Apartment Prices by Geographical Area.” Bulletin of Conjunctural Indicators (Tables II.7.1 and II.7.2). http:// www.bankofgreece.gr/BogDocumentEn/NEW_INDEX_OF_APARTMENT_PRICES_BY_GEOGRAPHICAL_AREA.PDF

Barboza, David. (2013). “2 Chinese Cities Move to Cool Overheated Housing Market.” New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/01/world/ asia/2-china-cities-move-to-cool-overheated-housing-market.html?_r50 Castle, Stephen. (2013). “Irish Legacy of Leniency on Mortgages Nears an

End.” New York Times. March 29. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/30/business/global/irish-legacy-of-leniency-on-mortgages-nears-an-end.html?pagewanted51&_r50&adxnnl51&adxnnlx51416733219-jtwy5oMO4R2KMnyWPPkTcQ

China Economic Review. (2014). “Too Many Central Business Districts, Not Enough Business.” China Economic Review. http://www.chinaeconomicreview.com/frank-chen-cbre-china-commercial-real-estate-developers

CNTV. (2014). China: Property Sector Continues to Decline in July. CNTV, August 18. http://www.globalintelligence.com/insights/geographies/asia-news-update/construction-property-development#ixzz3K4JQcbAX

Colliers International. 2010. The Knowledge Report. July. Greater China: Office and Residential. http://www.colliersinternational.com/Content/Repositories/Base/Markets/China/English/Market_Report/PDFs/GreaterChina-Q2-2010.pdf

Das, Satyajit. (2014). “China’s Debt Vulnerability.” Economonitor, April 9.http://www.economonitor.com/blog/2014/04/chinas-debt-vulnerability/

Davis, Bob and Esther Fung. (2014). “Housing Trouble Grows in China: Overbuilding by Real-Estate Developers Leaves Smaller Cities with Glutof Apartments.” Wall Street Journal, April 14. http://online.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702303456104579487790125203828

Davis, Bob and Dinny McMahon. (2013). “Xi Faces Test Over China’s Local Debt: Risks from Debt are Still Controllable, Audit Office Says.” WallStreet Journal, December 30. http://online.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702304591604579289771905130900

Davis, Morris A., Andreas Lehnert, and Robert F. Martin. (2008). “The Rent-Price Ratio for the Aggregate Stock of Owner-Occupied Housing.” Review of Income and Wealth, 54(2): 279–284. http://www.lincolninst.edu/subcenters/land-values/rent-price-ratio.asp

Economic and Social Research Institute (of Ireland). (2011). permanent tsb/ESRI House Price Index 1996—2011. http://www.esri.ie/irish_economy/historic-reports/permanent_tsbesri_house_p/?

Ellis, Howard S. (1941). Exchange Control in Central Europe. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Eurostat. (2014a). House Price Index (2010 5 100)—Quarterly Data.[prc_hpi_q] http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/product_details/dataset?p_product_code5PRC_HPI_Q. (Reach page by searching onGoogle for Eurostat and [prc_hpi_q])

——. (2014b). Construction of Buildings Statistics—NACE Rev. 2. [sbs_na_con_r2]. Table 4a on thewebpage.On newwebpage, under NACE_R2, click on “construction of buildings.” http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/statistics_explained/index.php/Construction_of_buildings_statistics_-_NACE_Rev._2

——. (2014c). Production in Construction—Annual Data, Percentage change. [sts_coprgr_a] http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/product_details/dataset?p_product_code5STS_COPRGR_A

FlorCruz, Michelle. (2014). “Developers in China Combat Real Estate Oversupply with Wacky Deals and Deep Discounts.” International Business Times, April 19. http://www.ibtimes.com/developers-china-combat-realestate-oversupply-wacky-deals-deep-discounts-1573307

Gaffney, Mason. (1986). “Why Research Ownership and Values.” In Property Tax Assessment: Processes, Records, and Land Values. Eds. Richard R.Almy and T. Alexander Majchrowicz, pp. 91–109. Chicago: Economic Research Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the International Association of Assessing Officers, in cooperation with the Farm Foundation.

——. (2009). After the Crash: Designing a Depression-Free Economy. Malden, MA: Wiley. Originally published in American Journal of Economics and Sociology 68(4):839–1038.

George, Henry. ([1879] 1979). Progress and Poverty. New York: Robert Schalkenbach Foundation. http://schalkenbach.org/library/henry-george/p1p/ppcont.html

Gyourko, Joseph, Yongheng Deng, and Jing Wu. (2010). “Just How Risky Are China’s Housing Markets?” VOX, CEPR’s Policy Portal. http://www.voxeu.org/article/just-how-risky-are-china-s-housing-markets

Harris, Diane. (2013). “Urban Land Prices Hit New Lows.” Kyero. http://news.kyero.com/2013/06/urban-land-prices-hit-new-lows/7234

Harrison, Fred. (1983). Power in the Land: Unemployment, the Profits Crisis, and the Land Speculator. New York: Universe Books.