Erie, Pennsylvania: Missteps and Next Steps (Part 1)

This saga is slowly unfolding in Erie, Pennsylvania. By slow, we mean since 1960. Continue reading to see how this story unfolds.

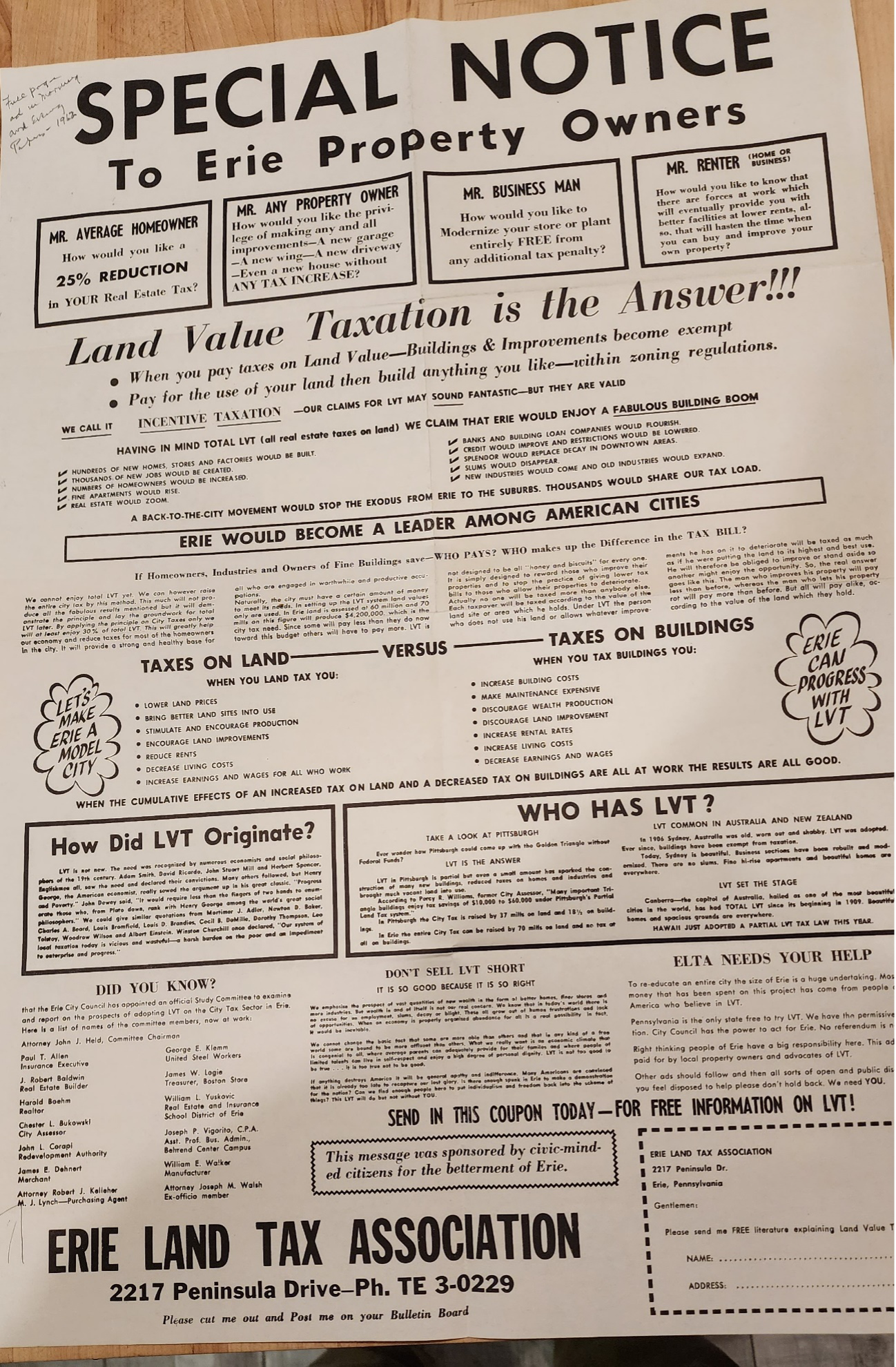

Since 1960, the saga of land value taxation is slowly unfolding in Erie, Pennsylvania. It was a couple of years after the passage of Land Value Tax (LVT) enabling laws for cities of the Third-Class code in Pennsylvania. It was also a time of action and of knee-jerk reaction. Nevertheless, forward-looking businesspeople, homeowners, and religious leaders gathered in their prosperous and growing cities to guarantee the stability and prosperity of their communities. Public education campaigns in Erie were exceptionally well-organized and popular.

The reactions of the old guard were predictable. First, “it’s communism.” Then, “it’s weird.” Third, “my uncle owns a vacant lot.” and most corrosive: “With all our industry and a bustling downtown, why on earth would we need a new tax system?”

Since the early 1960s, civic groups, elected officials, and citizens have been pushing for the City of Erie to adopt LVT. The impetus was changing the Third-Class City code, which permitted differential tax rates on land and buildings, signed by Governor David Lawrence in 1959.

Since the early 1960s, civic groups, elected officials, and citizens have been pushing for the City of Erie to adopt LVT. The impetus was changing the Third-Class City code, which permitted differential tax rates on land and buildings, signed by Governor David Lawrence in 1959.

In 1962, the Erie Times and Morning News both urged a serious study of LVT, and the Jaycees endorsed adoption. Proponents speaking before the council included the City Solicitor and City Assessor. In addition, renowned New Zealand parliamentarian, surgeon, and Labour Party official Rolland O’Regan visited Erie at the behest of the Erie LTA. Dr. O’Regan related the LVT experience in New Zealand and encouraged early adoption in Erie.

Also, in the early 1960s, The Erie Land Tax Association was formed to educate and persuade the city to adopt LVT. Members included local clergy members, business owners, and union leaders. Unfortunately, their approach to public outreach and education did not break through the “business as usual” wall, and the group became moribund soon. Around this time, the siren song of “urban renewal” helped put the boot in by demolishing much of the downtown and residential neighborhoods. The decline accelerated in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Then, elected officials like City Controller and future congressman Phil English, council President Michael Flatley and Councilman Mario Bagnoni pushed again for LVT, as did the City Planning Department; led by Daniel Borgia.

In 1982 the city commissioned a study of LVT: Headed by Professor An-Sik Min, Professor of Economics at Edinboro State College, the study concluded that LVT would benefit Erie’s citizens and commerce and stabilize the city’s revenue picture. Subsequent studies performed in 1988 and 2006 by the Center for the Study of Economics came to the same conclusion.

In 1990, City Council adopted LVT for the fiscal year 1991. However, then-Mayor Joyce Savocchio vetoed the measure. Reasons given were “unfamiliarity” with the concept (which surprised Council President Flatley, who noted in a Morning News article that Mayor Savocchio sat through four public hearings on LVT over her years on council). Other mayoral concerns were over loss of revenue (even though no other Pennsylvania city had encountered this).

Mayor Savocchio also ventured that Local Economic Revitalization Tax Assistance (LERTA) abatement projects already in place would be undermined by LVT. No credible rationale existed to support that claim. Two mayors who successfully used LVT (Harrisburg Mayor Reed and Washington, PA Mayor Spossey) asserted that it’s easier to grant LERTA and Keystone Opportunity Zone (KOZ) abatements under LVT. In addition, LVT can soften the projects’ financial hit when the abatements expire.

In the 1990s, the council raised LVT several more times, either as a guard against the negative impact of rising reassessments or as part of a more holistic economic development climate.

Another Opportunity, and Then Another

Would revisiting LVT make sense? Several factors have arisen since the early 1990s that make a compelling case for another serious study of the impact of LVT.

The inaccuracies of the 1969 assessment have been eliminated. In addition, the 2003 assessment made property values consistent within neighborhoods, land uses, etc. Therefore, the data are better than they have ever been. The computerization of records makes a parcel-by-parcel study of Erie’s tax roll much more straightforward. As of 1992, Third-Class School Districts coterminous with Third Class cities may also enact LVT. Therefore, the impact would be more significant.

Still Losing Population

Erie is still losing its population and is now older and more impoverished. The middle class in Erie – the bedrock of any community anywhere – has left the town in great numbers. The reduced tax base and its inability to provide sufficient revenue to fund city services is reason enough to look at LVT. Going from 138,000 people to 94,000 in a generation means holes in a city. And it’s not just vacant lots. In Erie, those holes are reducing revenues and exploring dangerous territories like increasing the local wage tax and raising fees and rates. Boosting a local sales tax should be a non-starter because Erie is known for welcoming shoppers from neighboring states with higher levies.

Erie has developed many projects to stimulate neighborhood and downtown revitalization. Yet, the “raising tides lifts all boats” thesis is difficult to realize when the areas around the projects are still burdened with tax levies that inhibit market growth.

Since the mid-2000s, we can now perform LVT studies and graphically present the information to the public with GIS mapping to make the effect clearer and easier to understand.

2023

This year, change is in the air. New faces and leadership are showing open minds to new ideas. The Erie City Council President Chuck Nelson was first elected to office, promising to look at LVT seriously. He’s done his homework and thinks he’s discovered why other postindustrial Pennsylvania cities have turned the corner. Looking at Allentown, New Castle, Harrisburg, and other LVT cities, he observed many upsides to the tax shift. Measurable benefits include both residential and non-residential sectors.

In Erie, instead of chasing diminishing returns, Council President Nelson is actively pursuing a new way.

Mr. Nelson and his ideas are both idealistic and achievable. Given Erie’s blessed geographic and economic location, Mayor Schember and Council are correct that the city has “good bones.” With a balanced diet of economic land rent, and avoiding the “carb rush” subsidies and temporary fixes, Erie may yet grab the brass ring.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!